Back

Back- September 29, 2025

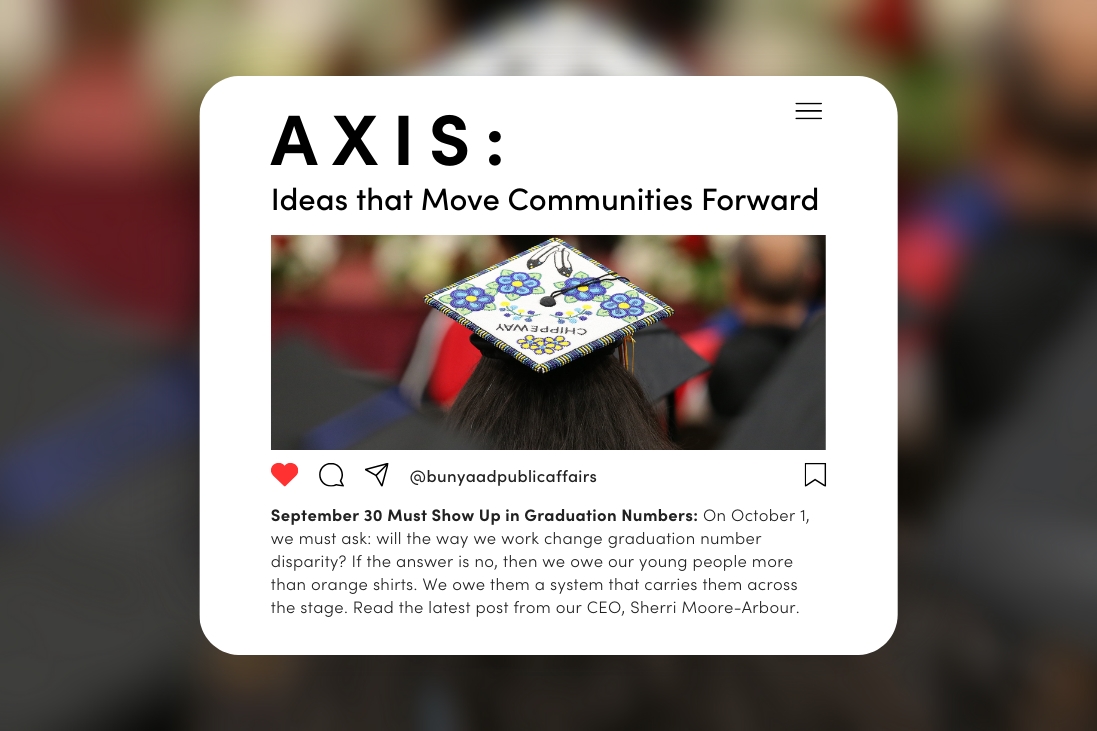

September 30 Must Show Up in Graduation Numbers

This year, September 30 cannot be just a ceremony. If reconciliation means anything inside our schools, it must be reflected in graduation rates for Indigenous students, not only in assemblies, morning announcements, and orange shirts.

The graduation gap remains severe. Statistics Canada’s latest data shows that only 63 percent of First Nations youth complete high school, compared with 91 percent of non-Indigenous youth. Living off reserve matters: 73 percent of First Nations youth off reserve have a diploma, compared with just 46 percent on reserve. Federal reporting is even starker: Indigenous Services Canada reports that only 30 percent of First Nations students on reserve graduated on time in 2023–24, with 49 percent graduating with extended time. Although on-time graduation has risen from 26 percent the year before, these numbers remain far from acceptable.

Provincial snapshots reinforce the urgency. In British Columbia, 64.3 percent of Indigenous students earned a Dogwood diploma in 2021–22. While it is an improvement from 58 percent five years earlier, it is still well below parity. Progress is happening, but too slowly.

The question is clear: what can we do on September 30 that moves these numbers in October and beyond?

In our work with school leaders, health partners, and policy tables, I return again and again to the distinction between relationships and jurisdiction. This distinction shapes contracts, funding, and authority. For Indigenous learners in provincial public schools, two tools are critical. Indigenous Education Enhancement (Equity in Action) Agreements create shared goals and accountability frameworks among districts, local Indigenous communities, and the ministry. Local Education Agreements specify services, funding, transportation, and reporting obligations between First Nations and boards of education. Together, these agreements form both a moral contract and a financial one. They are necessary foundations, but they are not enough to close the graduation gap.

A more transformational path is emerging in British Columbia through the First Nations Education Authority (FNEA). Since its launch on July 1, 2022, seven Nations have assumed full jurisdiction over education on their lands, collectively setting graduation requirements, certifying schools and teachers, and approving courses. This is a profound shift from advisory roles to true self-governance. Parallel processes with the BC Ministry of Education and Child Care ensure that courses can still count toward Dogwood credits, but authority over curriculum, assessment, and credentialing rests with the Nations themselves.

The FNEA model is young, and system-wide comparative data is not yet public. That creates an opportunity: publish clear, comparable measures annually for both FNEA and provincial systems, disaggregated by on/off reserve, on-time/extended graduation, and program participation. Transparent reporting is essential if we are to know whether reconciliation is working where it matters most: in the lives of young people.

The early advantage of the FNEA model is alignment. When a Nation sets graduation requirements and certifies teachers and schools, accountability sits exactly where it belongs. Curriculum and assessment reflect local languages, histories, and aspirations without requiring permission on the core questions that determine success.

In provincial systems, leaders must use Equity in Action agreements to set public, time-bound targets for Indigenous graduation rates and ensure Local Education Agreements make obligations for services, reporting, and outcomes unambiguous. In FNEA jurisdictions, governments and partners must support Nations to scale teacher certification, school certification, and graduation requirements and publish results openly so that others can learn from their progress.

Our role is practical: helping boards, superintendents, and ministry officials translate agreements into policy, budgets, schedules, and training that raise graduation numbers. Symbolism without results is no longer acceptable. Federal on-reserve graduation rates remain unacceptably low, provincial rates are improving too slowly, and the FNEA model offers a path to shift from partnership to true jurisdiction.

On September 30 we honour survivors and commit to action.

On October 1, we must ask: will the way we work change graduation number disparity? If the answer is no, then we owe our young people more than orange shirts. We owe them a system that carries them across the stage.

By Sherri-Moore Arbour

CEO, BUNYAAD Public Affairs

Back

BackRecent Post

Addressing Youth Vaping: Building Capacity, Not Dependency

- October 28, 2025

The work of prevention won’t be won by outsiders. Our Addressing Youth Vaping in Schools series equips educators with tools that match their world. Read how this approach builds capacity where students already feel seen and supported.

The Politics of Belonging: Alberta’s Parental Rights Debate

- September 26, 2025

Every child deserves to feel they belong. Yet in Alberta, fear is being used under the banner of “parental rights,” leaving some students behind. BUNYAAD’s latest editorial explains why this isn’t just politics—it’s about our shared responsibility as humans.

Prev Post

Prev Post